Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

I’d have to say that my favourite narrative, if not favourite game of all time is Half Life 2. There I said it. I named, irrevocably, my favourite game of all time without so much as an act of prosaic protraction or poetic lunacy. Above all, my measure of a favourite game comes from the game in which I think about revisiting most often. I am sure that the mere fact it isn’t STALKER has you trembling in your boots as a post without the name STALKER festooned across it is a post written by Jack. However, despite my tendency to wax lyrical, poetic et al about STALKER, Half Life 2 has always seized me within the grips of nostalgia as my mind wanders forth into its dystopian autocracy and refuses to leave.

Games aren’t movies. Why not?

Or books or television shows for that reason, and by that assumption, they shouldn’t be told in the same way, should they? When a movie wishes to tell a story, it will assemble the action before the eyes of the viewer in plain sight, where the visual cues rank in importance among the dialogue and the actions of the characters, and as the movie develops, these cues develop plot through exposition. As the viewer cannot assume a tangible role within the movie, the movie is forced to express itself excessively in order to engage the physically distanced viewer.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Conversely, when a book wishes to convey a story, it must use description to create the image that, in turn delivers the story, creating an experience that is partly filled in through the reader’s interpretation of the gaps and blanks, and their interpretation of the text. Games have the advantage of immediacy; having everything in the face of the player so that they do not have to create the world in their own mind, leaving more room for the delivery of a narrative.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

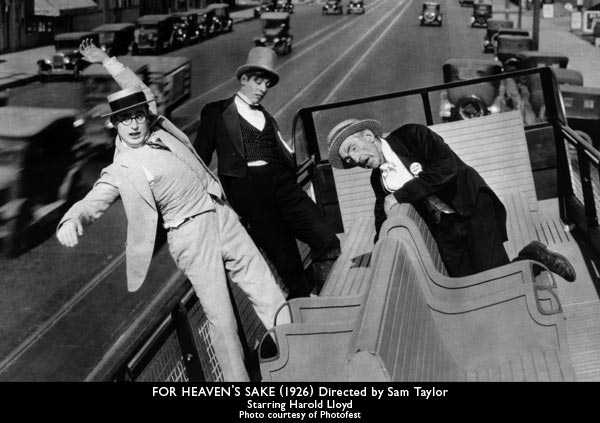

Games bear their narrative roots from those of film, television and novels; portraying the linear succession of story throughout the progression of the game. But even as stories become more complex, and games realise the potential for player agency within the story, the story is still being bound up within the “told narrative”; the great voice in the sky; a complete and utter contrivance. As movies require a connection between the film and the viewer to be established, a strong emphasis on how imagery alone can convey meaning has been established, stemming from the era of silent film. Silent film forced actors into rigorous pantomimes in visually exaggerated worlds, since it was all they had to express themselves. Even with the contemporary inclusion of sound, enabling complex delivery of narrative, these visual prompts are still used to great effect, and this is something I feel as if games are generally lacking.

The first thing you will notice about Half Life 2 is that it doesn’t have a story, per se. This isn’t to say it doesn’t have a narrative progression leading to an objective, it just doesn’t feel “written”. No, I lie, the first thing you will notice about Half Life 2 is the way the world expresses itself. The world feels alive, and as you slowly traipse through the opening level in pursuit of sanctuary, the game manages to assemble an image of what the world you have entered is with barely a spoken word of exposition.

A Combine scanner blinds you as it catalogues your face.

A patrol harasses a women as she pleads for her husband’s return.

“Don’t drink the water… they put something in it, to make you forget”.

A metro cop bursts into your abode, scattering the residents and peppering you will gunfire as you stumble through the wreckage.

Nobody is telling you the story. Nobody is treating you like anyone special. Everything is there for your interpretation.

Half Life 2 did what games have been losing the patience to do over the years – show don’t tell – in an effort that only seems logical. The game has at its disposal more than just imagery, but the ability to include you, the player as a tangible element within the world, so why not expose what the player requires through steady environmental cues and design?

Fortunately, Half Life 2 also realises that it is not a movie – something out of your immediate control – and never seizes the controls from you, unless the character is physically restrained. Although the transportation of theme from environment to player is very important, the player must be fully receptive to these themes and Half Life 2 has the player’s engagement at heart. The fact that the player is constantly engaged in the role of the character means that they are immersed and ready to receive the story in the same way that the film must prepare and ease the viewer into in so they can engage in the narrative.

So that is why I love Half Life 2. The wedding is next month.